All refrigerators running with gas relies on the principle that the evaporation of liquid to its corresponding gas form will take heat from surroundings. After evaporation, the gas should be liquefied back to liquid form to finish the cycle, and of course, the process of liquefaction will emit heat. That’s why need a fan (that’s just where the noise come from, which is also we want to diminish or even remove) for the commonly used gas-compression-based refrigerator to bring that part of emitted heat to the surrounding environment to keep it cool inside the refrigerator. The so-called absorption refrigerator, as one kind of gas-based refrigerator, also work on the evaporation and liquefaction of gas as mentioned above. But the difference here is that it does not bring the evaporated gas to its liquid form through compression. Instead, the evaporated gas will be solved (i.e. absorbed, thus comes the name ‘absorption refrigerator’) in some solvent, which then finish the cooling-and-heating cycle. [1, 2] General introduction to all kinds of refrigerators including the absorption refrigerator can be found everywhere on Internet, and a simple Googling will produce a lot of results [1-5]. Here in this post, I will focus on introducing a typical absorption refrigerator designed by Albert Einstein and his former student Leó Szilárd in 1926 and patented in US in November 11, 1930 [4]. This summary is created based on the following references: Ref [6, 7]. First of all, the picture demonstrating the basic design of Einstein’s frig from Wikipedia is presented here as following,

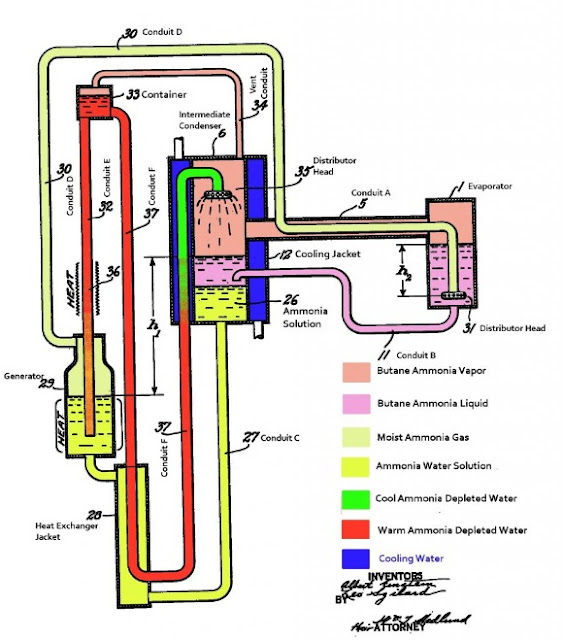

Figure. 1. The annotated patent drawing for Einstein’s fridge. Image reproduced from Ref. [4].

The working gas in Einstein’s frig is ammonia and butane ,and the absorption media is water which both ammonia and butane can be resolved in. As shown in Fig. 1, first of all, the ammonia gas is generated in the Generator (Fig. 1, No. 29), which is actually just a heater that heats the ammonia up to accelerate the evaporation of ammonia. Through Conduit D (Fig. 1, No. 30), ammonia gas will reach the Evaporator (Fig. 1, No. 1), which is the heart of Einstein’s frig and also where the cooling actually happens. Before going on, there are several key aspects to keep in mind, the first one is that unlike the electric frig, Einstein’s frig has the same pressure in all parts of the cycle. The second aspect is that the boiling point of certain matter (in this case specifically we mean butane contained in the Evaporator) decreases as the reduction of the corresponding partial pressure of that matter. In the first step of the cycle described above, we mentioned that the evaporated ammonia gas reaches the Evaporator, which naturally leads to the increasing of the partial pressure of ammonia. Also we already know that the pressure in all parts of the cycle keeps nearly as constant, and the total pressure is roughly the sum of the partial pressure of all component gas,

\[{P_{total}} = {P_1} + {P_2} + \cdots + {P_i} + \cdots\]

where \({P_1}\), \({P_2}\), etc. refers to the partial pressure corresponding to each single component in the system. As a result, with the introduction of ammonia into the Evaporator, the increasing of the ammonia partial pressure will lead to the reduction of the butane partial pressure. Then the boiling point of butane will decrease accordingly, which will lead to the evaporation of butane to cool itself and the environment. Here the ‘environment’ basically means part No. 5 in Fig. 1, where the food is kept.

The mixture of ammonia and butane will then flow to the Condenser/Absorber (Fig. 1, No. 6), where water is sprinkled (since the water Container – Fig. 1, No. 33 – is located higher in position than the sprinkle head – Fig. 1, No. 35, water can sprinkle automatically without problem) to absorb/resolve ammonia. Now the partial pressure of butane should increase accordingly when then lead to the condensation of butane (that’s why part No. 6 is also called the Condenser). The released heat accompanying the condensation then can be removed by the environment, e.g. by the flowing cooling water surrounding the Condenser, Fig. 1 – the blue-colored part surrounding the Condenser. In the Condenser, the ammonia-water solution and ammonia-butane liquid forms two layers because of the difference in density.

Here the ammonia-water solution in the Condenser is higher in position as compared to that in the Generator, which therefore promises the back-flowing of ammonia-water solution to the Generator automatically. In the way of flowing back to the Generator, the ammonia-water solution goes through the Heat Exchanger Jacket (Fig. 1, No. 28), where part of the heat carried by the ammonia-water solution is passed to the water in Conduit No. 37. Also, the water is heated in No. 36 Conduit, and I believe (although I am not sure and don’t have any supporting documents by hand) such heating may be beneficial for the circulating (this sprinkling) of water.

Although the environment contaminating gas feron used in the conventional compression-based frig has already been replaced by the environment friendly tetrafluoroethane (CH2FCF3) [5], the potability and miniaturisation are still big issues. For example, in some poor regions around the world where there is not much or even no electricity, portable frig is indeed necessary especially to keep vaccine cool before being used to save lives. In September 8, 2016, it was reported [8] the revamping of Einstein’s frig won researcher William Broadway the 2016 UK James Dyson Award. Also considering the noise-free property of Einstein’s frig, there are indeed reasons that we should believe the old invention still shines nearly a century later since its first coming-out.

References

[1] http://www.lafn.org/~dave/gas-frig.txt

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Refrigerator

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Absorption_refrigerator

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Einstein_refrigerator

[5] https://www.quora.com/Which-gas-is-used-in-refrigerators-nowadays

[6] http://blog.lib.uiowa.edu/eng/how-cool-is-this/

[7] https://grouptms2.wordpress.com/2012/03/16/working-principle-of-a-einsteins-refrigerator/