Talking about the magnetism of ions in crystals naturally brings us out of the atomic physics picture which we previously based ourselves in when discussing the free atom and ions (see previous note by clicking me!). Also, for sure we should turn to the many-electron scheme instead of a single-electron one. However, to build up the final multi-electron picture, we can potentially take the single-electron pathway. This is quite similar to the situation of independent atoms, where we have been mentioning the coupling between angular momentum of multi-electrons. The pathway we take thereby is also a single-electron one. For example, based on Hund’s rule, we talk about filling electrons one-by-one to various energy levels to finally build up the ground state. Here, for discussing the magnetism of ions in crystals, Hund’s rule can still be used in some situations. However, attention should be paid and we will revisit this issue later by inspecting a specific example.

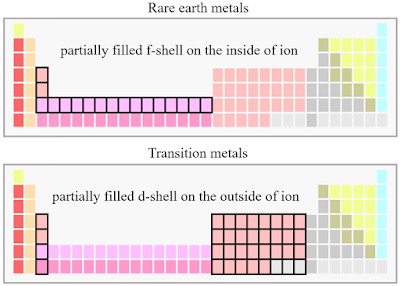

To start, we first notice that usually the orbitals involved in magnetism are either \(3d\) (e. g. transition metals) or \(4f\) (e. g. rare earth metals), both of which are strongly localized (as compared to, e. g. \(s\) orbitals). Therefore, we can still treat those ions as being isolated. However, they are not completely isolated as being free ions and the states will be more or less influenced by the surroundings.

Although we say both \(3d\) and \(4f\) orbitals are strongly localized, electrons in either of those states can still move in the whole crystal [1]!

In a broad sense, such effect upon states exerted by the surroundings in crystal can be called the crystal field effect, which has different pictures in two distinctive situations - \(3d\) orbital involved transition metal ions and \(4f\) orbital involved rare earth metal ions [1].

For rare earth metals, because overlapping between \(4f\) is weak and therefore the crystal field effect is also weak since it is purely coming from electrostatic potential. In comparison for transition metal, the \(3d\) orbital overlapping is much stronger and therefore the crystal field effect is also much stronger as the result of hybridization (see page 15 in [2]). In former case, the \(LS\) coupling is considered first to go into the coupled \(J\) representation and then the crystal field is considered to split the degenerate \(J\) levels. Hereby, it should be pointed out that in this case we directly go into multi-electron picture without going through the single-electron pathway as before! Detailed discussion can be found in page 15-18 in Ref. [2], where the magnetic anisotropy pops up naturally as the result of symmetry-adapted Hamiltonian (see page-18 in Ref. [2]).

For the latter situation, the crystal field effect is strong and thus is considered as the main factor, which splits the degenerate \(L\) levels. The \(LS\) coupling and other effects such as Zeeman effect are then considered as perturbations (see page 27-33 in Ref. [1]). Again, magnetic anisotropy naturally pops up as the result of either \(LS\) coupling or Zeeman term in the Hamiltonian (see page 34-37 in Ref. [1]). Moreover, Jahn-Teller effect also plays an important role for splitting states if the ground state is non-degenerate (see Ref. [3] and page section-3.4 in Ref. [1]).

Here we have two important things to mention. 1) When the ground state (see the example below for detailed explanations) is non-degenerate, it can be proved (see page 34-35 in Ref. [1]) that the contribution from orbital angular momentum (the coupled multi-electron one) to the Hamiltonian is 0. We say in such a situation, the orbital angular momentum is quenched. 2) When we have odd number of electrons, the doubly degeneracy of spin \(z\) component is not broken by the crystal field, which is called Kramers theorem and the still degenerate spin doublet is called Kramers doublet.

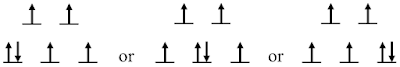

For understanding the splitting of \(L\) levels (which is obviously a multi-electron problem), here we can take a single-electron pathway. Taking the cubic symmetry as an example, first we can obtain the split states as the result of crystal field effect - the splitting into \(t_{2g}\) and \(e_g\) levels. Then according to the strength of the crystal field effect as compared to the energy for pairing electrons (the first Hund coupling, see previous note, by clicking me), we either have low-spin or high-spin situations - see Ref. [3] and page 21-22 in Ref. [2]. Suppose we have the low-spin situation, and for example we have 6 \(d\) electrons, the electrons can be filled into available states following the first Hund’s rule, as follows,

Any one of the three situations shown above can be our ground state and therefore in this case we have triplet degeneracy in our ground coupled state. Such a picture is exactly consistent with what we will get following the multi-electron approach, as shown in page 30-34 in Ref. [1].

Since we have hybridization of orbitals here, the single electron orbital angular momentum quantum number is no longer a good one. Therefore, the second Hund’s rule no longer works here and that’s why we have the triplet degeneracy in the example shown above.

Similar discussion can be made for other situations - refer to the states splitting discussed in page 19 in Ref. [2] and page 32-33 in Ref. [1].

For high-spin situation, we can also follow the single-electron pathway to discuss the degeneracy problems of the ground state. A full picture of electron configurations for both low-spin and high-spin situations can be found in Ref. [3]. N. B. when the energy difference between low-spin and high-spin configuration is not so large, we can potentially have the spin crossover - see page 21-22 in Ref. [2] - as the result of thermal effect.

References

[1] K. Yosida. Theory of magnetism. Springer. 1996.

[2] Theory of magnetism, by C. Timm.

[3] Jahn-Teller Distortions, from Chemistry LibreText.