When multiple atomic species (including vacancies) coexist on the same crystallographic site, it immediately brings up a question - say, we have species A and B sharing the same site, then do we have clustering of A and B in separate domains, or do we have A and B preferring to stay together, or do we have random distribution of A and B? This is usually what we mean by short-range order (SRO) and what we have mentioned here is specifically the occupational SRO (one can find introduction about more types of SRO in Chapter-10 in Ref. [1]). Detailed theoretical description about SRO can be found in Refs. [1-3] - the early paper by J. M. Cowley [2] gives the definition of SRO for binary systems; the one by D.De Fontaine [3] extends the definition to multi-component system (to give the so-called pairwise multi-component SRO, i. e. PM-SRO); the book by R. B. Neder and T. Proffen presents in details practical implementation and calculation of SRO, in DISCUS framework. Here I am not going to reproduce what has been covered in Refs mentioned here. Instead, only two main aspects, which I think is crucial for understanding the topic, will be recovered here.

In current blog, when we say SRO, we mean the Warren-Cowley (WC, or WC-like) coefficient.

📌SRO in terms of one-to-one connection VS shell

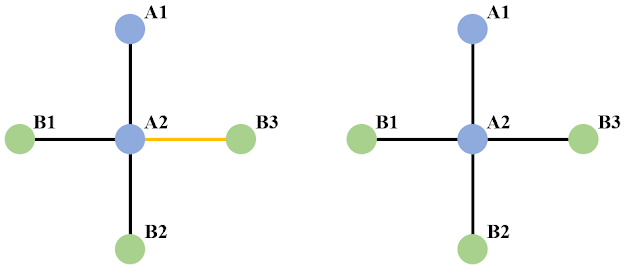

Taking the simple binary system shown above as an example, we have two types of atoms here - A and B. When we say SRO, we may mean the correlation between specific sites (left part of the picture above). For example, if we want to calculate the correlation between A and B along the [10] direction with A as the center, the only connection we have here is from A2 to B3, and vice versa for B (but now we focus on the connection along [-10] and the only connection we have here is from B3 to A2). In this case, the calculation for SRO is given as,

For A\(\rightarrow\)B,

For B\(\rightarrow\)A,

\[\alpha_{BA} = 1 - \frac{\bar{P}_{BA}}{c_A} = 1 - \frac{\frac{0+0+1}{3}}{\frac{2}{5}} = \frac{1}{6}\]

from which one can see the SRO with either A or B as the centering atom simply agrees with each other in quantity. Fundamental reason for this is that concerning the correlation along a certain direction, we have a one-to-one connection between A and B in question. This is exactly the case discussed in Ref. [2], concerning the pairwise correlation between species (the definition is not restricted to binary systems there).

However, when we say SRO, we could also mean the correlation in terms of shells, like shown in the right side of the picture above. In this case, the calculation for SRO changes to,

For A\(\rightarrow\)B,

For B\(\rightarrow\)A,

\[\alpha_{BA} = 1 - \frac{\bar{P}_{BA}}{c_A} = 1 - \frac{\frac{1+1+1}{3}}{\frac{2}{5}} = -\frac{3}{2}\]

Since in this case, the connection between A and B in terms of coordination shells is no longer a one-one-one connection, we therefore no longer necessarily have the result of SRO with A or B as the centering atom being equal to each other.

📌The limit value of SRO

According to the definition of SRO,

\(P_{AB}\) means the probability of find B around A, and \(c_B\) is the number concentration of B. Given fixed \(c_B\), the limit value of \(\alpha_{AB}\) is determined by \(P_{AB}\) which we know is a probability and therefore will range from 0 to 1 in theory. However in practice, we should have the following restriction for the value that \(P_{AB}\) can take,

\[P_{AB}\times N_A \leq N_B \Rightarrow P_{AB}\leq \frac{N_B}{N_A}\]where \(N_A\) and \(N_B\) refers to the total number of atoms of type A and B in the system, respectively. Then accordingly, we have,

\[\alpha_{AB} = 1 - \frac{P_{AB}}{c_B}\geq 1 - \frac{\frac{N_B}{N_A}}{\frac{N_B}{N_A + N_B}} = -\frac{N_B}{N_A}\]As the result of \(P_{AB}\) potentially not reaching its theoretical limit of 1, \(\alpha_{AB}\) may have a floor higher than its theoretical limit, accordingly. On the other side, we simply have,

\[P_{AB} \geq 0\]and therefore,

\[\alpha_{AB} = 1 - \frac{P_{AB}}{c_B} \leq 1\]References

[1] R. B. Neder and T. Proffen. Diffuse Scattering and Defect Structure Simulations: A Cook Book Using the Program DISCUS. Oxford University Press. (2008).

[2] J. M. Cowley. Phys. Rev. 77, 5. (1950).

[3] D. De Fontaine. J. Appl. Cryst. 4, 15. (1971).