📌Introduction - What is temperature?

By temperature (\(T\)), we could mean simply the ‘hotness’ of something, i. e. as always the case in our daily life, the higher \(T\) of an object, the hotter it is. But in physics, when we say temperature, we could also mean a parameter that is shared between systems when they reach equilibrium, in terms of heat flow. Quite often, these two specific meanings of temperature agree with each other. For example, in terms of heat flow, the natural (by which we mean no extra work needs to be done for it to happen, naturally) direction of heat flow will always be from hotter object (thus with higher \(T\)) to colder (thus with lower \(T\)) one. As heat flows out of the hotter object, its temperature (now, we mean ‘temperature’ by its first definition as given above) will decrease, and vice versa for the colder object. This process will continue until these two objects in question reach equilibrium ‒ they now share the same temperature and now, we mean ‘temperature’ by its second definition as given above.

📌Why is that we will never touch 0 K? Or, what does 0 K really mean?

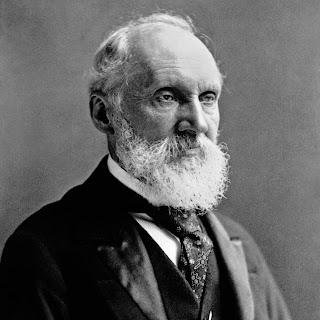

Concerning the first way of defining temperature, to get its definite value, one needs to set up a scale first. Usually, such systems will be used as the indicator of temperature that they respond differently and definitely to different temperature magnitude (i. e. the extent of hotness). For example, mercury will expand differently at different temperature so conventionally it is used as the medium of thermometer. Though thermometers like those made of mercury are used commonly, their disadvantage from the perspective of physics is obvious ‒ the definition of temperature scale depends on the properties of particular matter that is used as the medium for measuring temperature. Here, by ‘properties of matter’, we mean basically the amount of heat flow, given certain increase or decrease of temperature of the matter in question. Lord Kelvin then developed the idea of defining an absolute scale of temperature, vis a vis the uniqueness of temperature value in terms of heat flow [1]. The idea was originated from Carnot’s theory on ideal gas engine, whereby we have the relationship between the heat flow (in between working matter of high and low temperature) and temperature of working matters as follows,

\[\frac{Q_1}{Q_2} = \frac{T_1}{T_2}\]

Kelvin’s ideas was that if following Carnot’s principle of ideal engine to define temperature, it will be on an absolute scale then since as shown in the equation above, the heat flow only depends on the temperature of the working matter but nothing else. Saying this in another way, if we are using some other temperature scales (e. g. the mercury one and some other similar ones), the equation above will not simply hold universally in between the situations where different scale is used.

Knowing what we mean by absolute scale of temperature, we then need to know how we can obtain its value. To do this, we need to first know a fact that the absolute scale of temperature defined by Kelvin is identical to that defined on a special working matter ‒ among all the possible working matters that we can choose to use ‒ the ideal gas. The proof of this can be found in Ref. [2] (page 35-36). Then suppose we use \(T\) to represent the temperature, of ideal gas, in absolute scale and we have a parameter \(b\) for the transformation between absolute scale and conventionally used temperature scale (e. g. the Celsius scale), we then have the following famous expression (ideal gas law),

where, as we already know, \(R\) is a constant. Now suppose we fix our volume and the amount of matter in question (i. e. \(n\) in the equation above), we can then measure the change of pressure \(P\) versus the change of temperature \(T\). The constant \(R\) can thus be estimated. Once we know \(R\), we then proceed to seek for the zero point in the absolute scale - where the pressure goes to absolute 0 (which means all atoms are then staying statically and not moving) - by simply extrapolating the \(P\)-\((T-b)\) line from whatever \([P_x, (T_x - b)]\) point we measured the system at, to \((0, 0)\). That is to say,

\[b = T_x - \frac{P_xV}{nR}\]

Originally, the value of \(b\) was calculated to be around \(237.15\) [3]. In 1954, the resolution 3 of the 10th CGPM meeting defines one unit (K) of temperature in absolute scale equals \(1/237.16\) the interval between absolute \(0\) and the temperature of triple-phase point of water [4]. Hereby, we know the reason why the absolute \(0\) is EXACTLY \(-273.15\) degree in Celsius: the temperature of water triple point is DEFINED to be \(0.01\) degree in Celsius and also DEFINED to be \(273.16\) degree in absolute scale, which means simply the \(0\) degree in Celsius is EXACTLY \(273.15\) degree in absolute scale.

Back to the question in the section title - why we can never reach absolute \(0\)? As discussed above, \(0\) \(K\) is an assumed state with pressure of \(0\) and is proposed mathematically by extrapolating the ideal gas equation to \(0\) \(K\). In the assumed state, since we will have pressure to be \(0\), we will then have all atoms staying statically, which is obviously impossible - fundamentally due to the Heisenberg uncertainty principle.

📌But, why do we have negative temperature?

Now we know why absolute zero can never be reached, but sometimes we will come across negative temperature in literature. Wait…what??? We just said \(0\) \(K\) is even impossible, how will it be possible that we have negative temperature? To get an idea about negative temperature, we need turn back to the definition of temperature again, as we have already mentioned at the very beginning of this blog. Up until now, we haven’t talked about the second approach of defining temperature mentioned there ‒ temperature defined as the parameter shared in between systems in equilibrium. To discuss negative temperature, that’s something we have to go for now.

Suppose we have an isolated system containing two subsystems. The overall number of particles and energy of the whole system will be kept as constants, i. e. we have a microcanonical ensemble. Say we have the overall energy of the whole system to be \(E\) and the two subsystems are with energy of \(E_1\) and \(E_2\), respectively, we should then have \(E = E_1 + E_2\). Our question is then when, or in what condition can we say the two subsystems are in an equilibrium state, in terms of heat flow. Since we have an overall microcanonical ensemble, we know that the equilibrium state will be the one with maximum number of microstates. The total number of microstates of the overall system is given as,

where we have \(E_1\) and \(E_2\) as our variables of the function of microstates number, with the constraint that, as we mentioned above, \(E = E_1 + E_2\). Going a bit further, a famous quantity is defined to describe the number of states ‒ entropy, which originated from Boltzmann. In fact, entropy (\(S\)) is nothing but taking the log of total number of states of the system in question, to within a multiplicative constant ‒ Boltzmann constant \(k_B\). Now, the entropy of the overall system mentioned here in the context can be expressed as,

\[S(E_1, E_2) = k_Bln[N(E_1, E_2)]\]From the discussion above, we know that when the two subsystems reach equilibrium, we will have \(S\) to be stationary, with regard to infinitesimal change in \(E_1\) and/or \(E_2\), i. e.,

\[\begin{equation}\begin{aligned}dS & = dS_1 + dS_2\\ & = \big(\frac{dS_1}{dE_1}\big)dE_1 + \big(\frac{dS_2}{dE_2}\big)dE_2\\ & = \big(\frac{dS_1}{dE_1}\big)dE_1 - \big(\frac{dS_2}{dE_2}\big)dE_1\\ & = \big(\frac{dS_1}{dE_1} - \frac{dS_2}{dE_2}\big)dE_1 = 0\end{aligned}\nonumber\end{equation}\]Here there are two things to mention about the derivation. First, for the first line in the equation above, we have,

\[\begin{equation}\begin{aligned}S & = k_Bln[N(E_1, E_2)]\\ & = k_Bln[N_1(E_1)\times N_2(E_2)]\\& = k_Bln[N_1(E_1)] + k_Bln[N_2(E_2)]\\ & = S_1 + S_2\end{aligned}\nonumber\end{equation}\]The second thing is from the 3rd to 4th line in the same equation. Here we need to recall that \(E = E_1 + E_2\) is kept as a constant, and therefore we have,

\[dE = dE_1 + dE_2 = 0 \Rightarrow dE_2 = -dE_1\]Then from the equation \(dS = 0\) given above, we will have,

\[\frac{dS_1}{dE_1} - \frac{dS_2}{dE_2} = 0 \Rightarrow \frac{dS_1}{dE_1} = \frac{dS_2}{dE_2}\]Till here, we arrive at a quantity that is shared between two systems in equilibrium, which then becomes our theoretical definition for temperature \(T\),

\[T = \frac{dS}{dE}\]

For most systems, when its energy increases, the entropy will also increase ‒ as we pump energy into a system, the overall energy of atoms (or whatever building block of the system) within the system will increase. This will create more possibilities for the system, i. e. the number of states will increase as the result of energy increase. Therefore, in most cases, our definition for \(T\) will get a positive value. However, this may not be the case of some spin systems. Suppose we have \(N\) spins existing in magnetic field. The ground state will be that all spins pointing along the direction of the magnetic field (ignoring spin-orbital coupling for the moment), say, spin-up direction. As we flip over one spin from spin-up to spin-down, the system energy will for sure increase. As for entropy, flipping over one spin will change the entropy from \(S = k_Bln1 = 0\) to \(S = k_BlnC_N^1 = k_BlnN\), where we also have entropy increasing as the result of the spin flip-over. As we continue to flip over spins one by one, the increase of energy will continue. However, the increasing of entropy will stop when we reach the turning point of \(C_N^j\) function (of \(j\)), where \(j\) is the number of flipped-over spins ‒ \(j = N/2\) if \(N\) is an even number and \(j = (N\pm 1)/2\) if \(N\) is an odd number. Going over the turning point, the entropy will decrease as we continue to flip over spins. In this case, according to the definition of the theoretical temperature, \(T\) will become negative.

Furthermore, it should be pointed out that the negative temperature system is actually hotter than the positive temperature system. What does that mean? Imagine two systems touching each other, one of them is with negative temperature, and the other one with positive temperature. Now if energy flows from the negative-\(T\) system to the positive-\(T\) system, what will happen? The number of microstates (i.e. the entropy \(S\)) of the whole system will increase. Why? For negative-\(T\) system, when energy was taken away from it, \(S\) will increase since for negative-\(T\) system, entropy increases as the decreasing of energy. Similarly, the accepting of extra energy for the positive-\(T\) system will also lead to the increase of entropy, since for positive-\(T\) system, entropy increases as the increasing of energy. Therefore, when negative- and positive-\(T\) systems touch each other, the energy naturally tends to flow from the negative to the positive one, to maximize the entropy (thus to reach a more stable overall state) ‒ till the whole system reaches its equilibrium.

References

[1] Lord Kelvin (William Thomson), On an Absolute Thermometric Scale. Philosophical Magazine October 1848 [from Sir William Thomson, Mathematical and Physical Papers, vol. 1 (Cambridge University Press, 1882), pp. 100-106.]

[2] 汪志诚,热力学\(\cdot\)统计物理(第四版),高等教育出版社。

[3] Q & A on Zhihu, https://www.zhihu.com/question/54691426.