Image reproduced from Ref. [5].

In this blog, I will put down my learning notes as reading through the article on topological electrons by A. P. Ramirez and B. Skinner [1]. Basically, I will follow the story flow in Ref. [1] and therefore, first, I will note down the main flow that one can follow to arrive at the notion of topological electrons. Then I will cover the implications of topology and its connection to quantum Hall effect and quantum spin Hall effect. Finally, Weyl semimetal will be covered. It should be pointed that I will not reproduce all the nice discussions presented in Ref. [1]. Rather instead, I will just try to note down those key points or questions that I came across during reading Ref. [1]. First, the topological structure of an geometric object is defined by the Gauss-Bonnet integral,

\[\frac{1}{2\pi}\int_S K dA = n\]where \(K\) refers to the curvature at points on surface \(A\). The integral will give us a constant \(n\) which corresponds to the genus (number of holes) of a certain geometric object in the following manner,

\[n = 2(1 - g)\]When defining topological electrons, we are trying to look for similar definition as for the Gauss-Bonnet integral presented above. We can summarize the discussion in Ref. [1] as the following flow, Berry connection \(\rightarrow\) Berry curvature \(\rightarrow\) Berry phase. Considering then the integral of Berry curvature on the boundary of a 2D Brillouin zone, we then arrive at the topological invariant - the Berry phase,

\[\frac{1}{2\pi\hbar^2}\int_{BZ}\Omega d^2p = C\]where the topological invariant \(C\) in this case is called the Chern number. \(\Omega = \nabla \times \mathbf{X}\) is defined as Berry curvature, where \(\mathbf{X}\) is the Berry connection. The general definition for Berry connection and Berry phase can be found on Wikipedia [2] and won’t be reproduced here. Though, it should be pointed out that the general variable \(R\) in the formulation presented in Ref. [2] becomes \(p\) (i.e. momentum of electron) in the specific context of discussing topological electrons. Accordingly, the Berry connection in the context of topological electrons has its physical meaning - the average position of electron as the function of momentum. To understand this, we can refer to Eqn. (5.34)-(5.39) in Ref. [3].

In Ref. [1], it was briefly discussed that the

space of allowable momenta is called the Brillouin zone. Here is some side notes for the discussion with this regard. According to de Broglie, the momentum is related to the wavelength of the matter wave. In the context of eletrons, the momentum of electronsdescribes the process of hopping between beighboring crystal lattice sites(quoted from Ref. [1]), or put in the language of wave, thewavehere specifically refers to the wave of electrons which are surrounding the atoms and thus possessing the same underlying crystal lattice symmetry. In wave theory, we know that the wavelength actually refers to the periodicity in space and therefore the electron wave periodicty in space (i.e., the wavelength) cannot be smaller than the distance between neighboring unit cells of the crystal. Considering the de Broglie relation \(\lambda = 2\pi\hbar/p\), there is then an upper limit of the values that the momentum can take. From the perspective of Fourier transform, we know that the discreteness in one space yields periodicity in the coupled space. Therefore, we know that in the momentum space, beyond the first Brillouin zone, we will just have duplicates of the first BZ, for stuff of interest, e.g., the energy band.

In Ref. [1], it was mentioned that the definition of tbe Berry connection \(\mathbf{X}\) is

not gauge-invariant, and it is fundamentally due to that Bloch function involved in the Berry connection formulation is only defined up to a multiplicative phase factor \(e^{i\theta_{\vec{p}}}\). According to the Bloch theorem, the Bloch function in Ref. [1] refers to the real part of the electron wavefunction and since it is real, we can always write it as the modulus of a complex number which can have any arbitrary phase.

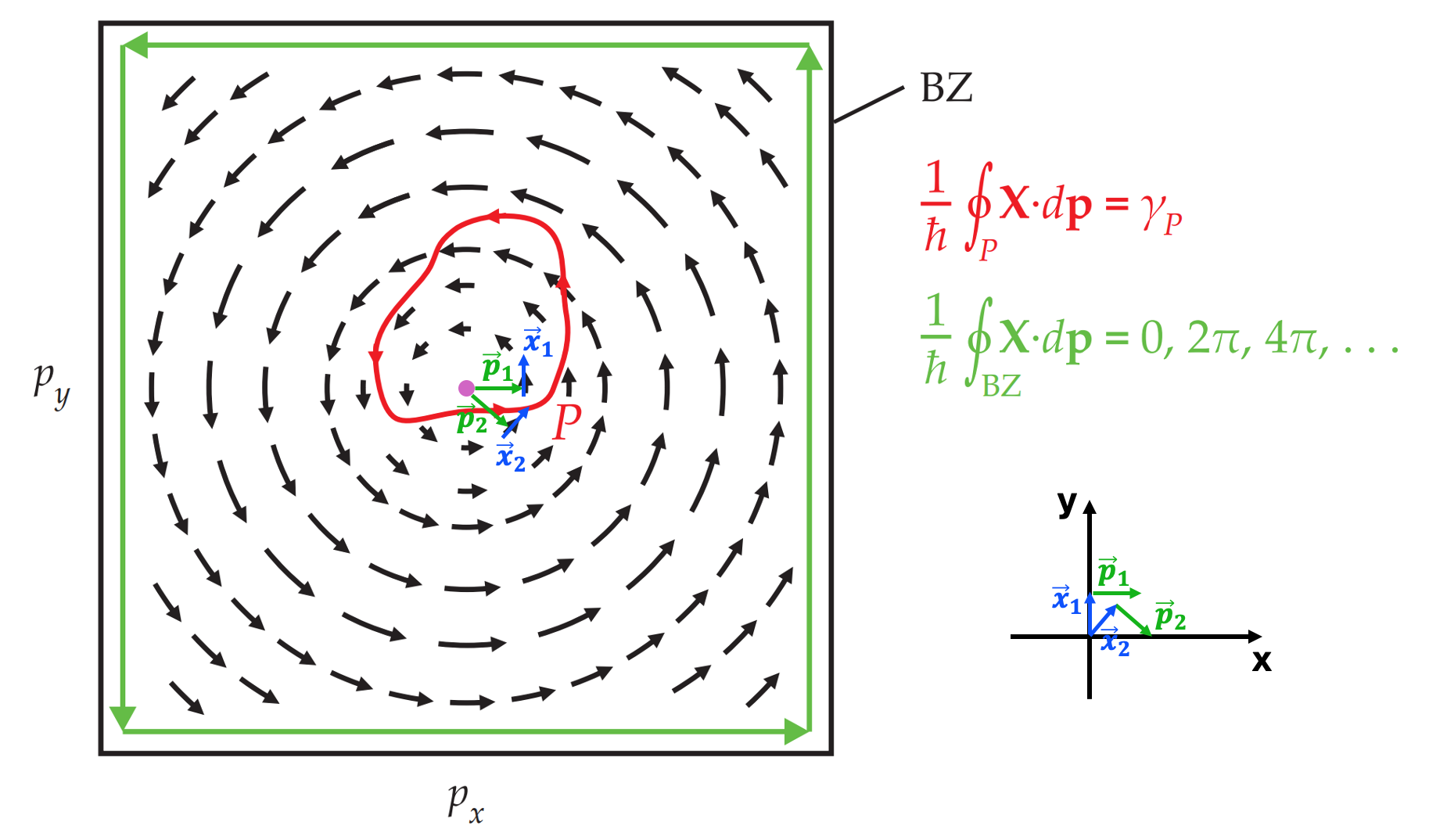

According to the Chern number formulation discussed above, it is fundamentally related to the phase factor associated with the Berry connection integration along a path \(P\) in momentum space. When the integration happens to be along the BZ boundary, we know that integrating along the clockwise and counterclockwise direction should yield physically equivalent states. However, meanwhile, the integration along the clockwise and counterclockwise direction should be giving negative phaes factor. Therefore, we know that the phase factor absolute value should be either 0 or an integer multiple of \(2\pi\) (physically equivalent to the state with phase factor of 0). Further, we know that to guarantee we have non-zero Chern number (i.e., non-zero path integration of the Berry connection), we should have \(+\vec{p}\) and \(-\vec{p}\) being inequivalent to each other, since otherwise, for any \(\vec{p}\) state, we would have a corresponding \(-\vec{p}\) state with identical Berry connection, which would make the integration always equal to 0. As a result, a non-zero Chern number would mean the Berry connection forms a “winding” or “self-rotation” pattern, as illustrated in Ref. [1]. As such, it infers that a system with non-zero Chern number implies intrinsic magnetic field.

Image reproduced from Ref. [1].

To see why the winding of Berry connection infers magnetic field, we can stare at the Fig. 3 in Ref. [1]. The figure is reproduced here with some further annotations to demonstrate the emergence of magnetic field. The figure shows the Brillouin zone in the momentum (i.e., reciprocal) space. Therefore the actual indication for the rotation of electrons in real space may not be as straightforward as shown in the figure, since visual rotation of arrows (the back ones) in the figure is happening in the the momentum space. To get an idea about the indication of rotation in the real space, we can map the figure onto the real space (with x and y as the axis), as shown in the bottom-right inset of the figure. Here we can pick two representative points in the momentum space (\(\vec{p}_1\) and \(\vec{p}_2\) in the figure). The corresponding Berry connection (i.e., the average position of the corresponding wavefunction) is shown to be \(\vec{x}_1\) and \(\vec{x}_2\), respectively. Then we can transfer all those vectors (both the momentum and position vectors) onto the coordinate system in the real space (again, the bottom-right inset), and now the indication of the rotation behavior is intuitively clear. Another way of looking at this may be a bit more mathematical – any vector field with non-zero curl infers some rotation behavior. For example, a paddlewheel in the flowing water will not rotate if the water is all uniformly flowing in the same direction (i.e., no curl). Once the curl is non-zero, the water flow will become non-uniform, leading to the rotation of the paddlewheel [4].

-

See also the highlights here in reading the blog post by A. P. Ramirez and B. Skinner – it is an excerpt from a draft of Ref. [1].

-

Also refer to the blog post here for a basic introduction to topological insulator.

References

[1] A. P. Ramirez and B. Skinner. Physics Today 73, 9, 30 (2020) – see also the saved page here.

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Berry_connection_and_curvature

[3] https://1drv.ms/b/s!AlZpbyasn9jtoqUZCYW069akHDG2rQ?e=gCynHc

[4] vector-calculus-understanding-circulation-and-curl/

[5] https://www.bnl.gov/newsroom/news.php?a=117401

[6] https://1drv.ms/b/s!AlZpbyasn9jtoqUlsQ_9KB7CG2g-og?e=kSOfZu

[7] https://1drv.ms/b/s!AlZpbyasn9jtoqUkYCO6KG6h8JZFFA?e=gdOCXB

[8] https://1drv.ms/b/s!AlZpbyasn9jtoqUj2N8fMFbK-0_cNQ?e=oe58FK

[9] https://jqi.umd.edu/glossary/quantum-hall-effect-and-topological-insulators

[10] https://scienceblogs.com/principles/2010/07/20/whats-a-topological-insulator