Size effect

The Bragg equation can be derived based on a simple picture where one can calculate the phase difference between the two sets of incoming and scattered beam corresponding to two scattering center. The fundamental idea is that when the phase difference is the integer multiple of the wavelength, one would have the diffraction maxima and thus the Bragg scattering condition. However, the actual scattering event can be pictured in a more general way, as described, for example, in the book by M. Dove (see section 6.3 in Ref. [1]). Based on the general picture of scattering event, the overall scattering intensity can be mathematically described as the summation of a series of plain wave, as given below,

\[F(\vec{Q}) = \sum_n exp(i\vec{Q}\cdot\vec{r}_n)\]Here, we are treating the scattering center as geometric points without size. In practice, the scattering center won’t be a point and the internal correlation within the scattering center could be described by a corresponding quantity representing its overall scattering strength. For X-ray, it is the form factor and for neutron, one has the scattering length. Mathematically, the expansion from a point scatterer to one with finite size can be described by convolution in real-space and according to the property of Fourier transform (calculating the scattering intensity following the equation above either in a discrete or continuous manner is equivalent to Fourier transform from the mathematical perspective), such a convolution will corresponding to a multiplication in reciprocal space. Therefore, considering the finite size effect of the scatterer only yields a multiplicative factor to the formulation above. For the purpose of discussion in this article, such a multiplicative factor won’t make any real difference and thus will be omitted here in the context.

As the simplest case, if we consider a one-dimensional chain of scatterers arranged in an equally-spaced manner, the overall scattering intensity can be calculated as presented below, according to the formulation above and assuming the space between adjacent scatterers is \(\vec{a}\) (a vector point along the 1D chain) and overall we have \(N\) atoms [2, 3],

\[\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} I(\vec{Q}) & = |F(\vec{Q})|^2 = |\sum_{n=0}^{n=N}exp(i\vec{Q}\cdot\vec{r}_n)|^2\\ & = |\sum_{n=0}^{n=N}exp[i\vec{Q}\cdot(\vec{r}_0 + n\vec{a})]|^2\\ & = |exp(i\vec{Q}\cdot\vec{r}_0)|^2\times|\sum_{n=0}^{n=N}exp(i\,n\vec{Q}\cdot\vec{a})|^2\\ & = 1 \times |\sum_{n=0}^{n=N}exp(i\,n\vec{Q}\cdot\vec{a})| \times |\sum_{n=0}^{n=N}exp(i\,n\vec{Q}\cdot\vec{a})|^*\\ & = \frac{1 - e^{i\,N\vec{Q}\cdot\vec{a}}}{1 - e^{i\vec{Q}\cdot\vec{a}}} \times \frac{1 - e^{-i\,N\vec{Q}\cdot\vec{a}}}{1 - e^{-i\vec{Q}\cdot\vec{a}}}\\ & = \frac{2 - (e^{i\,N\vec{Q}\cdot\vec{a}} + e^{-i\,N\vec{Q}\cdot\vec{a}})}{2 - (e^{i\vec{Q}\cdot\vec{a}} + e^{-i\vec{Q}\cdot\vec{a}})}\\ & = \frac{2 - 2cos(N\vec{Q}\cdot\vec{a})}{2 - 2cos(\vec{Q}\cdot\vec{a})}\\ & = \frac{2 \times 2sin^2(\frac{N\vec{Q}\cdot\vec{a}}{2})}{2 \times 2sin^2(\frac{\vec{Q}\cdot\vec{a}}{2})}\\ & = [\frac{sin(\frac{N\vec{Q}\cdot\vec{a}}{2})}{sin(\frac{\vec{Q}\cdot\vec{a}}{2})}]^2 \end{aligned} \end{equation}\]Here we are calculating the quantity corresponding to the experimentally measured intensity which is associated with the square of the amplitude. \(\vec{r}_0\) here represents the position of the first atom in the series.

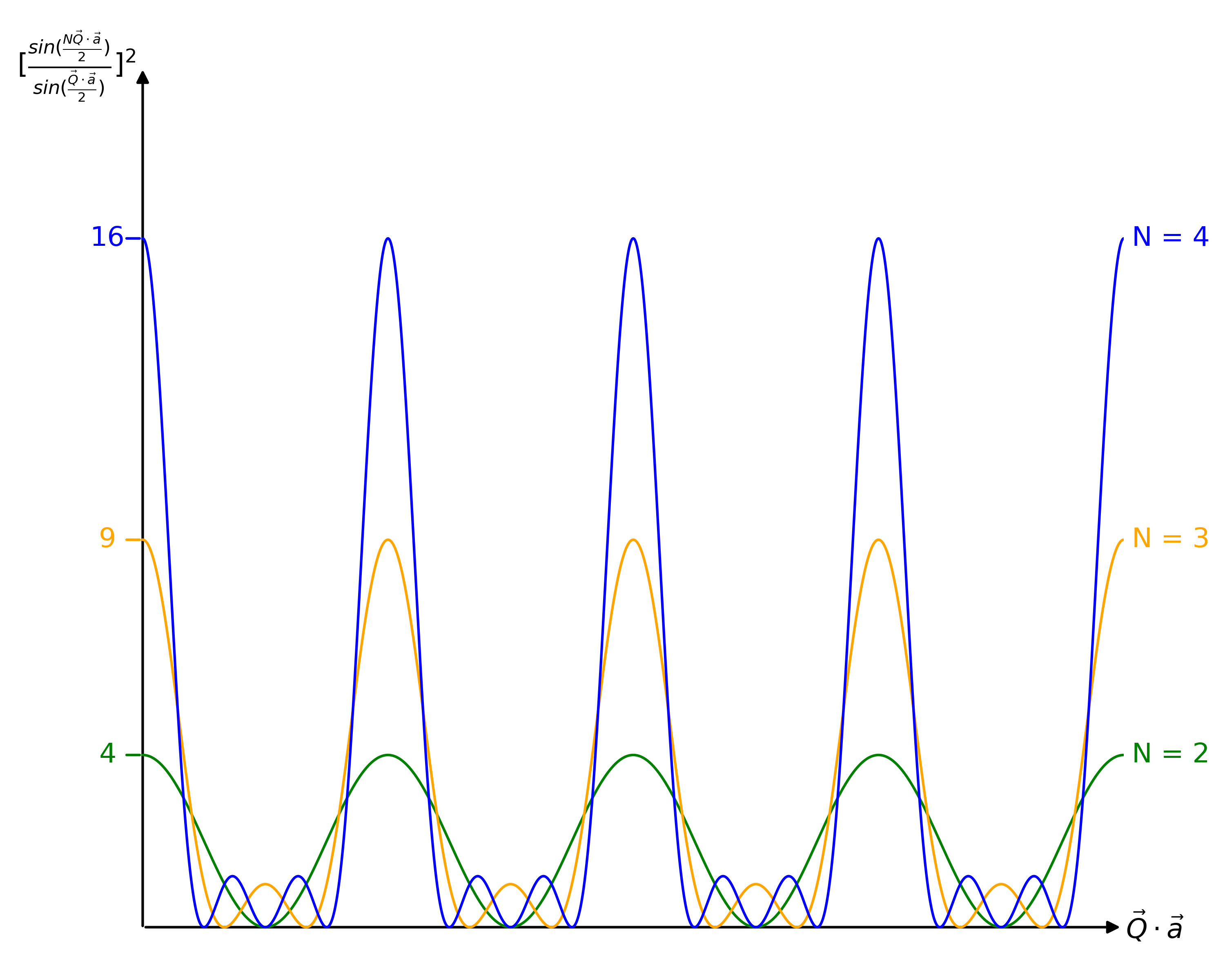

The resulted intensity corresponding to the scattering of the 1D chain of atoms can be plotted as below, as the function of \(\vec{Q}\cdot\vec{a}\) (fundamentally, the function of the scattering vector \(\vec{Q}\)),

Here for the demo purpose, we consider the situation where \(N = 2, 3, 4\).

Two things that can be told from the plot are,

-

The diffraction peaks are located at certain locations, and from the mathematical expression above, one can arrive at the condition as \(\vec{Q}\cdot\vec{a} = 2\pi n\), where \(n = 1, 2, 3, \dots\). Considering the magnitude of \(|\vec{Q}| = \frac{4\pi sin\theta}{\lambda}\), one can simply arrive at the Bragg equation from the peaking condition here.

-

As the number of scatterers (\(N\)) involved in the 1D chain increases, the resulted diffraction peak becomes sharper, until reaching a delta function when \(N\) approaches infinity. Put the other way round, as \(N\) decreases, the diffraction peak becomes broader, demonstrating clearly the finite size effect upon the diffraction peak broadening.

The python script used for generating the plot here can be downloaded following this link.

Beyond the simplest 1D case presented here, the general relation between the finite size of samples and the diffraction peak broadening is given by the Scherrer equation,

\[\tau = \frac{K\lambda}{\beta\,cos\theta}\]where \(\tau\) refers to the mean size of the ordered domains, \(K\) is a dimensionless shape factor, \(\lambda\) is the wavelength of the scattering beam, \(\beta\) is the line broadening at half the maximum intensity (FWHM), after subtracting the instrumental line broadening, in radians, \(\theta\) is the Bragg angle. The derivation of Scherrer equation based on the scattering intensity formulation presented above can be found in Wikipedia [2].

Strain effect

Assuming we have a crystal with infinite size, we would have the diffraction peaks as described by the summation of a series of delta functions, meaning infinitely sharp diffraction peaks. However, in practice, if we have strain effect in our crystal, the lattice will be distorted as compared to the ideal situation, meaning the spacing between lattice planes will be changed as compared to the ideal crystal. In such a situation, the Bragg condition will be met at different location in reciprocal space, i.e., the diffraction peaks will shift their positions. If then we have inhomogeneously strained crystals, the scattering peak will be distributed around the nominal position (without strain) and the end result is the diffraction peak broadening. Detailed explanation and illustration could be found in Ref. [4].

Since both the size and strain effect could lead to the broadening of diffraction peaks and in practice there comes the natural question how we are going to decouple the two effects and derive the size and strain of our samples independently. There are two main solutions based on different level of assumptions, namely the Williamson-Hall plot and the Warren-Averbach method. The former one is a coarse solution, based on the simple assumption that the overall peak broadening is simply a summation of the contributions from the two, whereas the second one is in general a more rigorous solution. The details of both solutions can be found in Ref. [5].

Preferred orientation and Texture

For powder diffraction, we ideally assume having a polycrystalline sample where lots of small crystalline samples uniformly orient in space. When shining a beam on such a polycrystalline sample and collect the diffraction signal using a 2D detector, one would have the diffraction rings corresponding to the Bragg conditions for different lattice planes. Spots long each diffraction ring corresponds to a small piece of crystalline sample orienting along a certain direction. If those small crystalline samples are indeed uniformly distributed in the polycrystalline sample, the scattering intensity extracted from those diffraction rings is representative and the relative intensities corresponding to different lattice planes can be linked by their corresponding structure factor. However, if for some reason the distribution of those small crystalline samples is non-uniform, the scattering intensities extracted from the diffraction rings are not comparable to each other according to the structure factor. Instead, the relative intensity is associated with both the structure factors and the number of small crystalline samples orienting in different directions. In practice, we have two typical such situations – preferred orientation and texture. The former one is more of a systematic effect, i.e., the sample systematically prefer to grow along a certain lattice direction whereas the second one refers specifically the case where there are insufficient crystallites to provide a true powder diffraction pattern. Both situations will lead to the incomplete coverage of the diffraction rings where the coverage of different diffraction rings is different across different lattice planes. More detailed discussion could be found in Ref. [6, 7].

References

[1] M. Dove, Structure and Dynamics: An Atomic View of Materials. Oxford University Press. 2002.

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scherrer_equation

[3] http://pd.chem.ucl.ac.uk/pdnn/diff1/scat1d.htm#link1

[4] http://pd.chem.ucl.ac.uk/pdnn/peaks/size.htm

[5] http://pd.chem.ucl.ac.uk/pdnn/peaks/sizedet.htm