In crystallography, quite often we would use the 6 lattice parameters to describe the unit cell, namely, a, b, c, \(\alpha\), \(\beta\) and \(\gamma\). In some cases, we would also need to construct those lattice vectors (\(\vec{a}\), \(\vec{b}\) and \(\vec{c}\)) in Cartesian coordinate system. For example, when we want to put atoms into the unit cell, we would have to have those lattice vectors given in the Cartesian coordinate so that atom coordinates can be easily obtained. Here in this blog, I will present a generic derivation for how to construct the lattice vectors in the Cartesian coordinate system, from the 6 lattice parameters.

It should be noticed that in practice, we would have different choices of convention to put the lattice vectors in the Cartesian coordinate system. Here, we will first put the \(c\)-axis along the \(z\)-axis. Then, we put \(b\)-axis in the \(y\)-\(z\) plane, with the \(y\)-axis project always positive. Finally, we put down the \(a\)-axis, with the \(x\)-axis project always positive.

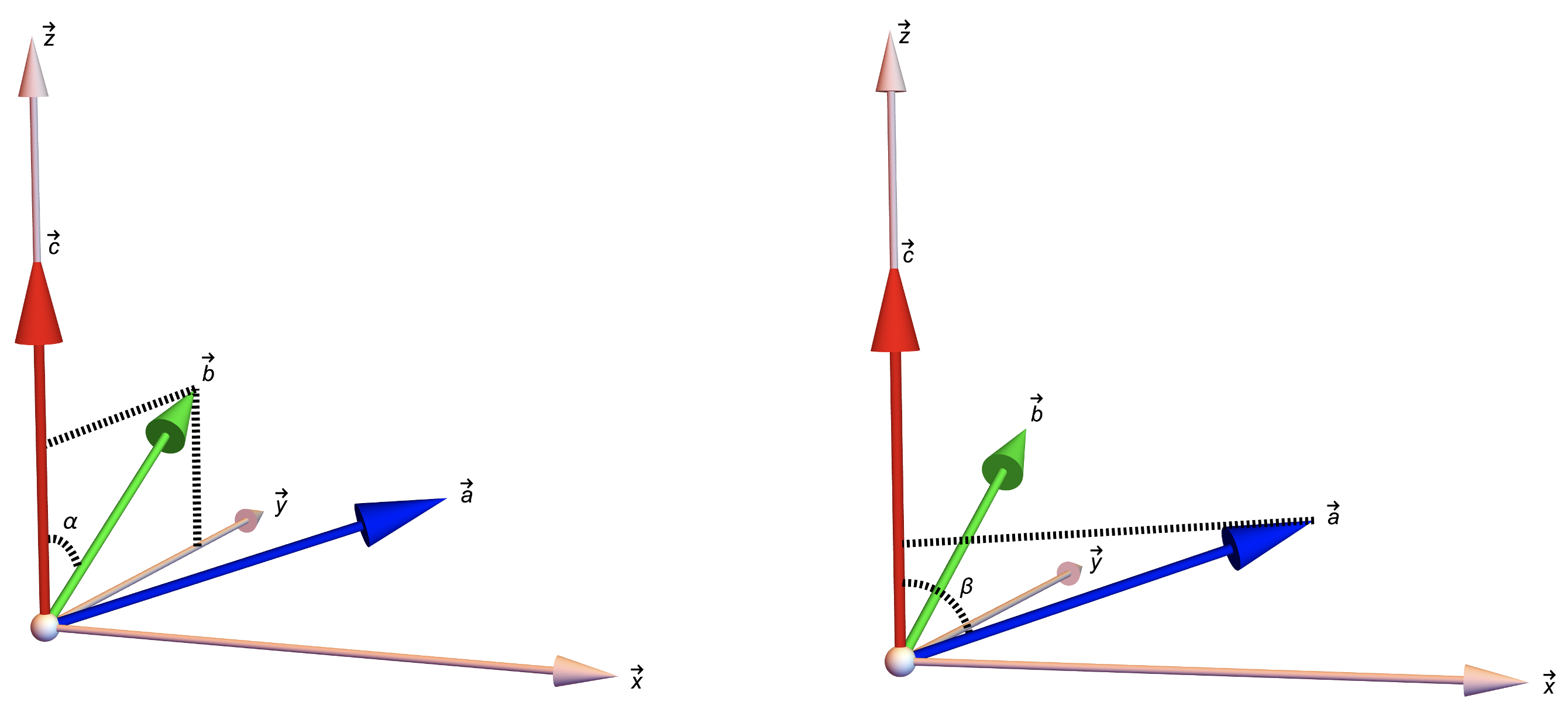

Lattice vectors projection in the Cartesian coordinate system. The left panel shows the \(b\)-axis projection and the right panel shows the \(a\)-axis projection.

Lattice vectors projection in the Cartesian coordinate system. The left panel shows the \(b\)-axis projection and the right panel shows the \(a\)-axis projection.

First, it is straightforward to put down the lattice vector \(\vec{c}\) as,

\[\vec{c} = c\,\vec{\hat{z}}\ \ \ \ (1)\]where \(\vec{\hat{z}}\) refers to the unit vector along the \(z\)-axis, and the same symbol also applies for \(x\)- and \(y\)-axis. Since \(\vec{b}\) is put in the y-z plane and therefore, it is also straightforward to write down the projection of $$\vec{b}$ as,

\[\vec{b} = b\,sin\alpha\,\vec{\hat{y}} + b\,cos\alpha\,\vec{\hat{z}}\ \ \ \ (2)\]As for \(\vec{a}\), first, as seen from the right panel in the picture above, the projection onto the \(z\)-axis can be straightforwardly written down as \(a_z = a\,cos\beta\). So, we can write down \(\vec{a}\) as,

\[\vec{a} = a_x\,\vec{\hat{x}} + a_y\,\vec{\hat{y}} + a\,cos\beta\,\vec{\hat{z}}\ \ \ \ (3)\]with \(a_x\) and \(a_y\) to be determined. Further, given the vector form of \(\vec{b}\) and \(\vec{a}\) presented in Eqn. (2) and (3), we can write down their dot product as,

\[\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} \vec{a}\cdot\vec{b} & = (a_x\,\vec{\hat{x}} + a_y\,\vec{\hat{y}} + a\,cos\beta\,\vec{\hat{z}})\cdot(b\,sin\alpha\,\vec{\hat{y}} + b\,cos\alpha\,\vec{\hat{z}})\\ & = a_yb\,sin\alpha + ab\,cos\alpha cos\beta\\ & = |\vec{a}|\cdot|\vec{b}|\cdot cos\gamma\\ & \Rightarrow ab\,cos\gamma = a_yb\,sin\alpha + ab\,cos\alpha cos\beta\\ & \Rightarrow a_yb\,sin\alpha = ab\,cos\gamma - ab\,cos\alpha cos\beta\\ & \Rightarrow a_y\,sin\alpha = a\,cos\gamma - a\,cos\alpha cos\beta\\ & \Rightarrow a_y = \frac{a(cos\gamma - cos\alpha cos\beta)}{sin\alpha}\ \ \ \ (4) \end{aligned} \end{equation}\]Finally, \(a_x\) can be easily calculated as,

\[a_x = \sqrt{a^2 - a_y^2 - a_z^2}\ \ \ \ (5)\]So, we would have,

\[\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} \vec{a} & = \sqrt{a^2 - \Big[\frac{a(cos\gamma - cos\alpha cos\beta)}{sin\alpha}\Big]^2 - a^2cos^2\beta}\,\vec{\hat{x}} + \frac{a(cos\gamma - cos\alpha cos\beta)}{sin\alpha}\,\vec{\hat{y}} + a\,cos\beta\,\vec{\hat{z}}\\ \vec{b} & = b\,sin\alpha\,\vec{\hat{y}} + b\,cos\alpha\,\vec{\hat{z}}\\ \vec{c} & = c\,\vec{\hat{z}} \end{aligned} \end{equation}\]