Normally for a powder sample, we are assuming that we have a uniform distribution of orientation of those small crystalline samples, meaning that we have many small crystalline pieces of the sample and their orientation in space is uniform. As such, in the measured powder diffraction pattern, the peak intensities are representative for the structure factor, from which we can then perform detailed structure analysis. When those small pieces of crystals are not oriented uniformly in space, the powder sample is not ideal for obtaining a diffraction pattern that is a clean representative of the underlying structure factor. In this case, the intensities of some of the diffraction peaks are preferrably enhanced, and therefore one cannot directly extract structure information given the measured peak intensities, if not teasing out such preferred intensity enhancement. In practice, we have two types of such a situation – preferred orientation and texture. The former situation is more systematic, meaning that the sample intrinsically prefers to have certain lattice plains orient towards a certain direction relative to the sample. The latter situation is a bit different. Though, reflected in the preferred enhancement of the diffraction peak intensities, the latter one is quite similar to the former case, however, texture means that we have imperfect powder samples, and such an imperfection comes in a random way. For example, if we grind and sieve the sample, we may find that the powder diffraction pattern measured each time may be a bit different.

Taking the constant wavelength diffraction as an example, as we scan through the \(2\theta\) scattering angle, for each direction along the Debye-Scherrer cone (with the same scattering angle), we are expecting crystal orienting in such a way that the measured lattice plane (that agrees with the Bragg condition, givne the constant wavelength and \(2\theta\)) normal direction is pointing along the \(\vec{Q}\) to be able to contribute to the measured Bragg peak. So, if the polycrystalline sample is not distributing uniformly, the proportion of the sample contributing to different Bragg peaks will be different from peak to peak. This fundamentally causes that the Bragg peak intensities not cleanly represents the structure factor.

In the case of texture, if we can rotate the sample freely and continuously in space, we can still obtain a reasonble powder diffraction pattern. The extreme case would be where we have a single crystal sample. In case of single crystals, if we want and if we are able to, we can rotate the single crystal continuously in space and integrate out the continuous diffraction spots in a ring to obtain the powder diffraction pattern. Imagine for constant wavelength beam and we have an area detector, when the single crystal is orienting in such a way that a certain lattice plane is satisfying the Bragg condition to create a diffraction spot at a certain scattering angle. Then we can rotate the single crystal sample continuously around the direction perpendicular to the area detector (or, parallel to the incoming beam direction) and we can obtain a diffraction ring without problems. This is for sure the extreme case and for a single crystal sample, there is no reason to make such redundant powder diffraction measurement at all.

In the case of preferred orientation, althogh we can still do the measurement just like described above to obtain a normal powder diffraction pattern. However, this does not mean the preferred orientation itself is removed. As mentioned earlier, the preferred orientation is an intrinsic characteristics of the sample itself and it is systematic. Also, quite often, we may just want to study such preferred orientation to learn about the preferred lattice plane orientation relative to certain directions of the sample. For example, for a rolling steel example, we would define three typical directions – normal direction (ND) which is perpendicular to the rolling steel plane, the rolling direction (RD) that lies within the rolling steel plane, and the cross direction (CD, also called transverse direction ,TD) that is perpendicular to both of the above two directions.

Pole figure is quite often used to characterize the preferred orientation or texture. Selecting a direction relative to the sample as the reference direction, we can plot the distrubtion of the scattering intensity of a certain HKL peak as the function of the sample orientation (relative to the selected sample direction). Experimentally, for constant wavelength beam, we can set up the diffraction measurement in such a way to measure a specific lattice plane (by adjust the scattering angle to meet the Bragg condition). Then relative to the selected sample reference direction, we can measure the distribution of the scattering intensity of the selected lattice plane as the function of the sample rotation in space and such a distribution can be projected onto to a 2D plane – this is just giving us the pole figure.

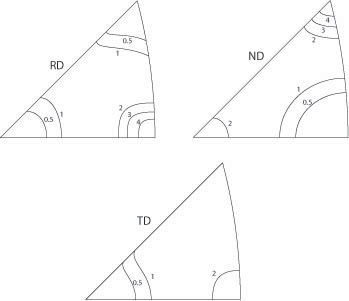

Inverse pole figure is another way to characterize the preferred orientation or texture. For the pole figure, we are looking towards the sample reference coordinate system, e.g., the pole direction (the direction pointing from inside the paper to outside) presented at the center of the pole figure could be the normal direction (ND) of the sample. For the inverser pole figure, it is the other way round – we are looking towards one of the crystal axes and check how the sample reference directions (ND, RD and TD) are distributing, and for sure, usually such a distribution is presented on a 2D plane through, e.g., stereographic projection.

Image reproduced from Ref. [6].

The figure above shows the three poles, namely the one for ND, RD and TD, respectively. The way to read the figure will be something like this,

-

RD Plot (Rolling Direction):

-

The contours peak at level 4 near the bottom-right corner.

-

Meaning: The crystal’s [101] direction is strongly aligned with the Rolling Direction.

-

-

ND Plot (Normal Direction):

-

The contours peak at level 4 near the top corner.

-

Meaning: The crystal’s [111] direction is strongly aligned with the Normal Direction (perpendicular to the sheet).

-

-

TD Plot (Transverse Direction):

-

The contours show a peak (level 2) near the bottom-left corner.

-

Meaning: The crystal’s [001] direction is aligned with the Transverse Direction.

-

References

[2] Intro to X-ray Pole Figures

[3] Quantitative texture analysis by Rietveld refinement

[4] Pole Figure-Texture Experiment - JIAM Diffraction Facility

[6] https://www.doitpoms.ac.uk/tlplib/crystallographic_texture/texture_representation.php