In the age of AI, is it really making any real sense to write blogs to put down something that AI can probably generate in a flash? In fact, when I was writing this blog, initially I was using the phrase ‘in a blinking time’ but as a non-native English speaker, I am not sure whether it is a suitable phrase to use so I turned to AI for suggestions and it gives me back a better alternative ‘in a flash’. So, thank you AI. This starts to become a bit ironic now – I want to say that writing blog is still necessary but I am actually relying on AI to complete the post. Indeed, a bit ironic, but still I keep writing, regardlessly.

I rememeber I ever came across some posts talking about whether writing blogs is already out of date in the AI age. Unfortunately I could not recall where the post is. But a quick Google gives me quite a few posts on this – they are interesting and I put links to them here [1, 2]. Some of the points hit exactly what I have been thinking – writing blog posts is more for myself to record my learning. To me, it is all about I spend time on a topic, digest all kind of resources, including those by AI, to the best I can at that moment, and then write them down. Without writing down, I always feel like all the digestions, right or wrong, will just slip away, which would make a terrible feeling. So, anyways, although AI can probably provide a way better explanation of the topic here, still I want to post it – in fact, I read about the topic about Goldstone mode with the help from AI, a lot.

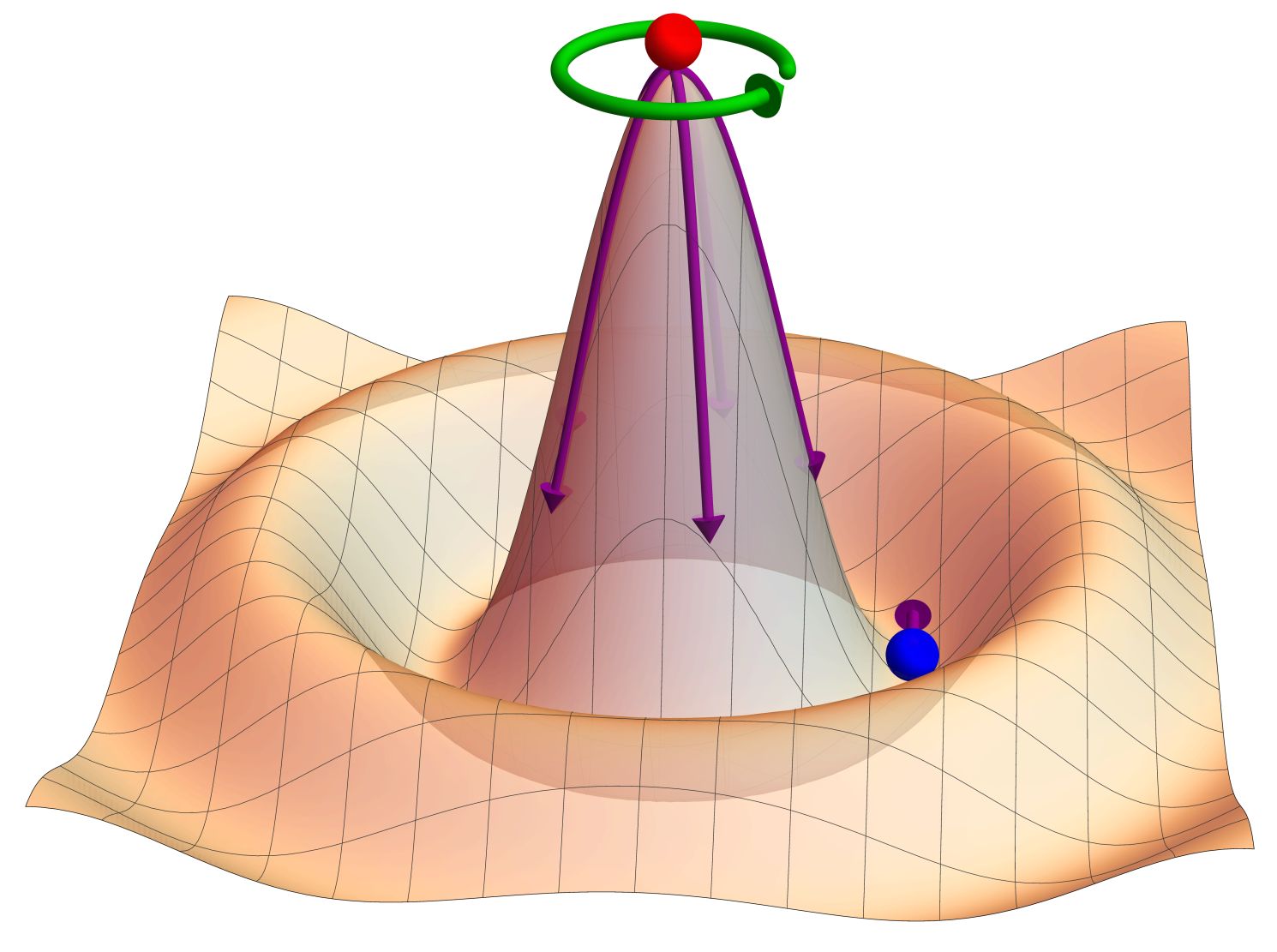

The Goldstone mode fundamentally is about two things – 1) continuous symmetry and 2) spontaneous symmetry breaking. The Goldstone theorem says if a continuous symmetry of a physical system is spontaneously broken, there must exist a massless mode in the spectrum of excitations [3, 4]. Concerning the continuous symmetry, we all know symmetry – when applying a transformation/operation to a physical system, the system keeps invariant (i.e., stay the same). For example, a piece of A4 paper has the \(C2\) symmetry – if we rotate the paper by 180° around the center of the paper, it will look like exactly the same as before the rotation. Such a type of symmetry operation is discrete – we can only rotate the paper by an integer multiplication of 180° to keep the paper invariant under the rotation. Meanwhile, the paper also has translation symmetry – for example, if we move the paper to the right by some distance, we cannot tell the difference of the paper. Imagine the paper is put in an infinitely large empty space without any other references. Before the translation, we enter the empty space and take a look at the paper and then walk away. After that, another person goes into the empty space and move the paper to the right by some distance. Then we enter the space again – now, without any references, we cannot tell whether the paper has ever been moved at all. This is symmetry, and this is the continuous symmetry since the paper can be moved to the right by any amount, i.e., by \(x \in \mathbb{R}\), assuming \(x\)-axis is defined as the right. Similarly we can have the continuous rotation symmetry – imagine we cut the A4 paper into a perfect circle and then rotation of the circle around its center by any \(\theta\) keeps the circle invariant. Here I am going to use the continuous rotation symmetry as the example to demonstrate the idea of the Goldstone mode. Assuming we have a hill of the Mexican hat shape, as shown below,

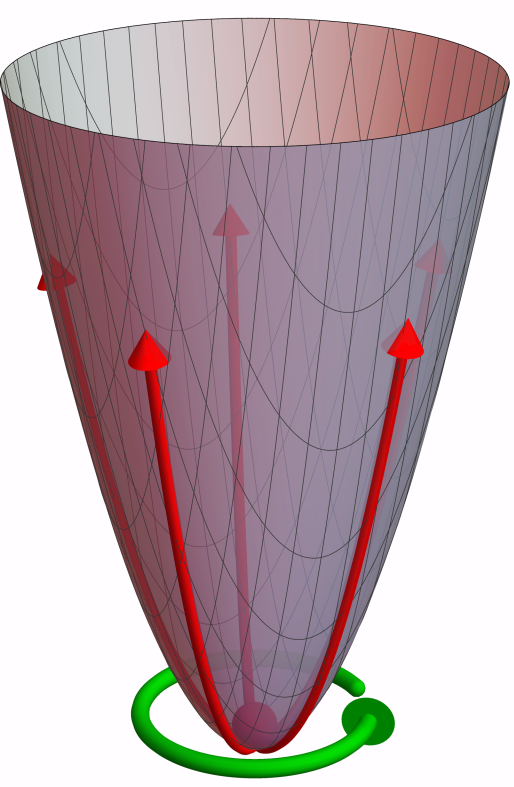

We have a ball sitting at the top of the hat initially. Such a state has continuous rotation symmetry as indicated by the green circulating arrow, obviously The physics dominating such a system also has the continuous rotation symmetry, meaning that the Newtonian physics does not have a preference for which direction that the ball should be going down the hill, i.e., all the arrows along the surface as shown in the image are equivalently possible. With such a setup, it is also obvious that the system is unstable – any tiny bit of disturbance, e.g., an infinitesimally small force \(\epsilon_F\) exerted on the ball is able to break the current state of the system and the ball will be rolling downhills. Finally, the system will rest in the stable state where the ball sits at the bottom of the brim, as shown by the blue ball in the image. As such, the continuous rotation symmetry of the system is broken – if we now rotate the system by any amount, the state will be different from what it is now, due to the ball now sitting at a specific spot at the bottom of the brim which is assymmetric under rotation. As such, we say the system shows spontaneous symmetry breaking, i.e., the continuous rotation symmetry is broken in a spontaneous way. Why spontaneous? Because as mentioned, it is ‘super easy’ to disturb the original unstable state of the system (where the ball sits at the top tip of the hat) so the original system tends to spontaneously break the rotation symmetry to arrive at a new and stable state. In another word, the external world needs to spend infinitesimally small amount of ‘efforts’ (energy) to break the continuous rotation symmetry. As a comparison, we can take a look at another situation – a valley of parabolic shape as shown below,

where again we have a ball now sitting at the bottom of the valley. Such a system obviously also has the continuous rotation symmetry. The difference here is the system now is stable – if there is no external force exerted on the ball, it will never leave this stable state spontaneously. In anther word, we don’t have the spontaneous symmetry breaking for such a system.

Gathering the two pieces, 1) ontinuous symmetry and 2) spontaneous symmetry breaking, we are now ready to talk about the Goldstone mode. Back to the first image above, once the continuous symmetry is spontaneously broken and the system rests in the stable state, we can nudge the blue ball towards the tangential direction along the brim bottom, as shown by the arrow attached to the blue ball. Again, the force we need here is infinitesimally small. Such a new state formed in an effortless way is the basic idea of the Goldstone mode. This is a reflection of massless excitation as presented in the definition of the Goldstone mode, i.e., changing the system state to the Goldstone mode is an effortless process, meaning that the energy needed for the state hopping is tiny.

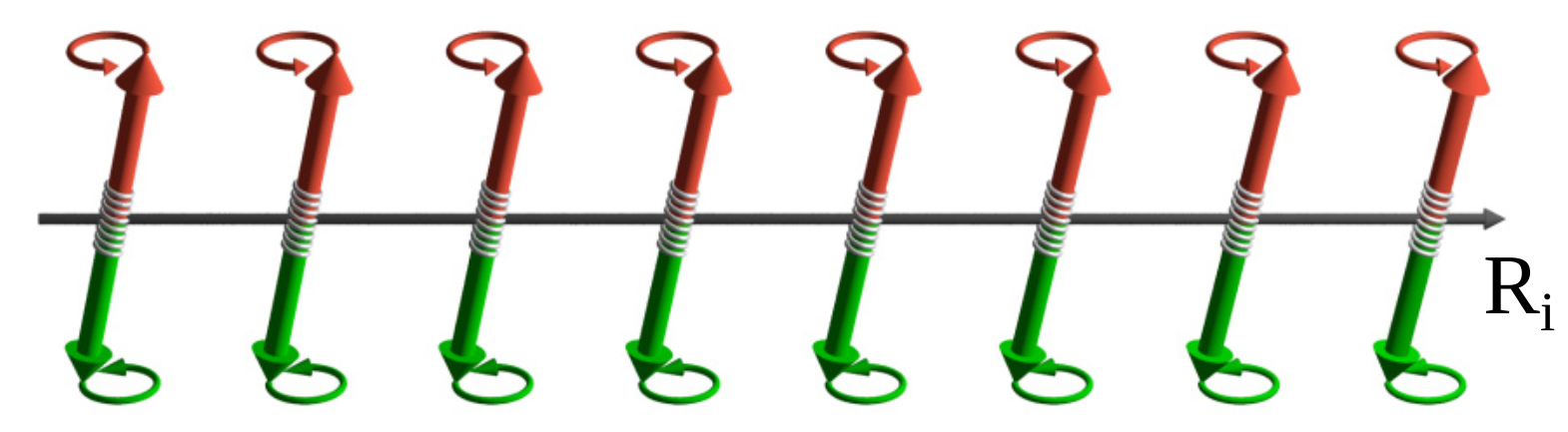

A good example of such excitation is the magnon excitation at \(k \approx \Gamma\) (long wavelength extreme), e.g., as shown in the image below,

(Image reproduced from Ref. [5])

Originally, the system prefers to rest at the ground state where all spins are aligned parallel to each other. Without anisotropy (e.g., due to the spin-orbital coupling), the polarization direction can be arbitrary in 3D space. This analogously corresponds well to the Mexican hat example above – the blue ball position is just the parallel alignment state of spins and just like the blue ball can be arbitrarily sitting at any position at the brim bottom, the spin polarization direction can be arbitrary in 3D. The Goldstone model of magnon excitation in this case then refers to the situation shown in the image (ignore the difference between the red and green arrows for the moment) – spins on each site is tilted a tiny bit differently so that locally adjacent spins almost align in a parallel way so that the energy needed for such an excitation is tiny (the corresponding magnon is therefore massless). As such, the wave corresponding to the varying tilt from spin to spin is with a very long wavelength, i.e., very slow oscillation. In reciprocal space, this correspond to the region close to the \(\Gamma\) point. In another word, the periodicity (wavelength \(\lambda\)) in real space is very large and accordingly the ‘space frequency’ (wave vector \(k\)) is very small.

Here I am attaching the Mathematica notebook used for creating the demo images in the post, Ref. [6].

References

[1] https://www.gilesthomas.com/2025/02/blogging-in-the-age-of-ai

[2] https://dev.to/lovelacecoding/why-blogging-still-matters-in-the-age-of-ai-438b

[3] Chat with Gemini about symmetry, Goldstone mode, etc.

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Goldstone_boson

[5] Markus Weißenhofer and Alberto Marmodoro, PHYSICAL REVIEW B 110, 094427 (2024)